[vc_tabs width=”2/3″ el_position=”first”] [vc_tab title=”The Vaddukoddai resolution”] [vc_column_text pb_margin_bottom=”no” pb_border_bottom=”no” width=”1/1″ el_position=”first last”]

Full text of VKR

…This convention resolves that restoration and reconstitution of the Free, Sovereign, Secular, Socialist State of TAMIL EELAM, based on the right of self determination inherent to every nation, has become inevitable in order to safeguard the very existence of the Tamil Nation in this Country…..

[/vc_column_text] [/vc_tab] [vc_tab title=”1977-TULF election Manifesto “] [vc_column_text pb_margin_bottom=”no” pb_border_bottom=”no” width=”1/1″ el_position=”first last”]

Full text of election manifesto of Tamil United Liberation Front -1977

…Hence the Tamil United Liberation Front seeks in the General Election the mandate of the Tamil Nation to establish an independent sovereign, secular, socialist State of Tamil Eelam that includes all the geographically contiguous areas that have been the traditional homeland of the Tamil speaking people in the country….

[/vc_column_text] [/vc_tab] [/vc_tabs] [vc_column_text title=”Solidarity Day-June 4th” pb_margin_bottom=”no” pb_border_bottom=”no” width=”1/3″ el_position=”last”]

Unite the union

128 Theobalds Rd

London

WC1X 8TN

Email: info@tamilsoloidarity.com

Phone: +44 (0) 7908050217

Reserve your place

[/vc_column_text] [box title=”The Vaddukoddai resolution and its place in history” type=”whitestroke” pb_margin_bottom=”no” width=”1/1″ el_position=”first last”]

-Manny Thain, National Coordinator for Tamil solidarity

The Vaddukoddai resolution (VKR) was adopted on 14 May 1976 at a conference bringing together the main Tamil groups calling for a socialist Tamil Eelam, a separate Tamil homeland. Both the date and the resolution have gone down in history – with the formation of the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) and its commitment to struggle for independence, arms in hand if necessary.

The VKR reflected the mood of a new generation of activists, radicalised by mass workers’ movements, revolutionary uprisings and guerrilla struggle around the world. It called for a separate Tamil homeland, which would give equal rights to all citizens, on the basis of what it called ‘decentralised democracy’. The caste system would be abolished in a secular state, where Tamil would be the national language but where Sinhala language rights were also guaranteed.

The final point of the Vaddukoddai resolution summed up the aspirations of those at the conference, as well as the radicalisation that was taking place. It declared: “That Tamil Eelam shall be a Socialist State wherein the exploitation of man by man shall be forbidden, the dignity of labour shall be recognised, the means of production and distribution shall be subject to public ownership and control while permitting private enterprise in these branches within limit prescribed by law, economic development shall be on the basis of socialist planning and there shall be a ceiling on the total wealth that any individual or family may acquire.”

In short, it was a very radical view for a new, egalitarian society. The momentous VKR did not fall out of a clear blue sky, however. It was the culmination of a long process of political developments: from the struggle against colonial rule under the British empire, to the nature of Ceylon after independence was declared on 4 February 1948, and the subsequent struggles of class, caste and ethnic forces.

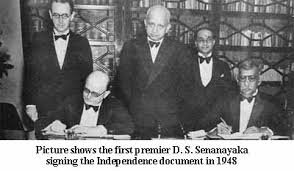

Facing mounting opposition and revolt, it became clear even to the British rulers that they could no longer maintain control of the island. At the end of the second world war, in 1945, Ceylon became a dominion – a self-governing part of the British empire. Independence was won in 1948, although Ceylon only formally shook off its dominion status in 1972, when it became known as the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.

The new independent state

Of course, Sri Lanka was never a socialist state, but the naming of the country as such was significant nonetheless. It reflected the strength of the mass movements of the workers and poor. It also reflected the popularity of socialist ideas at the time. Socialism was seen as a viable alternative to colonial rule, capitalist and landlord exploitation, and to oppression on the basis of ethnicity, religion, caste, gender, etc. People were demanding radical improvements in living and working conditions, along with a fundamental change in the way society was run.

Independence had offered up the opportunity to start anew, to break from the oppressive divide-and-rule policies which were the hallmark of the British empire. The British state had long mastered the art of playing off minority and majority populations against one another, and of taking advantage of other potential sectarian divisions, such as over caste and religion, in order to control and exploit its worldwide empire.

The newly independent Ceylon could have been set up on the basis of the recognition of the right to self-determination, alongside the protection of the rights of any minority in all areas. A voluntary federal system in which the island’s resources and decision-making were shared equally and peacefully, in cooperation and solidarity, could have been on the agenda. Of course, that did not materialise.

On the contrary, the Sinhalese political establishment – like a parasite on the backs of the majority population – sought to use its position to concentrate power in its hands. It would not be long before it showed how willing it was to whip up Sinhala chauvinism, unleashing thugs to attack Tamils and Tamil Muslims, as it attempted to consolidate its control.

However, the degree to which the Sinhalese political establishment was able to carry this out was dependent, ultimately, on the strength of the mass movements. For instance, the general strikes in 1953, 1962 and 1980 cut across the sectarian divisions by mobilising united, island-wide struggle. After all, whether Sinhala, Tamil, Upcountry, Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, Christian, or from any other background for that matter, all workers, poor and oppressed people have to struggle for decent pay, accommodation, education, training and health, and for democratic rights, land reform, etc.

The most dangerous times were when these mass movements stalled or were in retreat. That was precisely when the Sinhalese political establishment would relaunch attacks on workers’ rights and conditions, while whipping up Sinhala chauvinism, inciting violent assaults and pogroms against Tamil-speaking people – echoing the divide-and-rule policies of the former colonial masters.

The fact of the matter is that the Sinhalese political establishment represented an elite layer – the wealthiest at the top. They saw it as their right to rule following the independence of Sri Lanka. They did not seek to govern in the genuine interests of the majority of people on the island. Rather, they used their position of power as part of the majority ethnic group to attempt to seize control, to become the new capitalist and landlord class. Most Sinhala people were exploited workers and poor, used as pawns in the elite’s power-struggle game.

Mass opposition

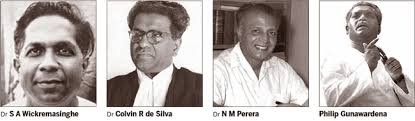

It is extremely important to recognise that the Sinhalese elite faced massive opposition to its attempt to dominate the political landscape. It was by no means certain that it would succeed. Above all, mass opposition to the rising capitalist/landlord class was led by the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), which called for the socialist transformation of society. It was, in fact, the first political party to be set up in Ceylon – back in 1935. It was not until 1946 that the Sinhala capitalists had formed their own party, the United National Party (UNP). A split from the UNP, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), was formed in 1952.

In the initial decades of its existence, the LSSP organised workers and middle-class activists all over the island: Sinhala, Tamil, Tamil Muslim, tea plantation workers. It had played a major role in mobilising mass action against British colonial rule, and supported the right of Tamils to self-determination following independence. On numerous occasions, LSSP members courageously defended Tamil-speaking people against violent mobs.

Unfortunately, over time its leadership lost sight of the need for independent, non-sectarian organisation – based on the organised working class and mass campaigns – and began to dilute its socialist programme. The leadership’s emphasis shifted from mass mobilisation to an over-reliance on parliamentary elections. Indeed, the LSSP first entered a coalition government with the SLFP as early as 1964, compromising its political principles for ministerial positions.

Under pressure from the Sinhalese political establishment, the LSSP also began to distance itself from the Tamil struggle. Certainly, in the period running up to the Vaddukoddai resolution in 1976, it was less and less able to attract the radicalising layer of Tamil youth. Although inspired by revolutionary movements around the world, these activists had been let down by the failure of the LSSP and workers’ movement to bring about fundamental change in Sri Lanka. They also rejected the rotten compromises of the established Tamil leaders. As a consequence, the Tamil youth were drawn increasingly towards a determined, armed struggle for an independent state.

Fast-moving times

The situation in the Tamil organisations reflected the deep changes taking place in society. Under British rule, Ganapathipillai Ganaser Ponnambalam’s All Ceylon Tamil Congress (ACTC) called for 50-50 representation (50% Sinhala, 50% other ethnic groups) in the state council set up by the empire. This was not in any way a call for Tamil independence, however, or even for an end to colonial rule. It was, in reality, an attempt to accommodate the Tamil struggle within the British empire. Ponnambalam was jostling for position to claim to be the representative of the Tamils – on behalf of a section of an upper-caste Tamil elite.

The logic of this position was seen in the first Ceylon parliament after independence, when Ponnambalam joined the government coalition under Don Stephen Senanayake’s UNP. With his own comfortable position secured, Ponnambalam quickly threw the demands for Tamil rights out of the window of his ministerial office. This was the trigger for the setting up in 1949 of the Federal Party (FP – the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kadshi), under the leadership of Samuel James Vellupillai Chelvanayagam. In coalition, the ACTC backed all of the UNP’s measures attacking workers’ rights and conditions. Needless to say, these measures also hit Tamil workers, including on the tea plantations, hard.

When DS Senanayake died in 1952, his son, Dudley, took over. It was a short-lived position, as a huge general strike and hartal shook the whole country in August 1953, in protest at attacks on working and living standards. Reeling under the blows from this generalised movement of the workers, the government fled to a British warship in Colombo harbour. Dudley Senanayake was forced to resign. This could have been the moment when the government was brought down, and a revolutionary constituent assembly put in its place – with genuine representation of and participation by all the people, reflecting the needs and defending the interests of the workers and poor of all ethnic and religious backgrounds.

That golden opportunity was missed, however, and this failure would have huge consequences for the forces of the left, above all, the LSSP and the workers’ movement. Having regained control, the new UNP-led government under John Kotelawala went back on the offensive. The notorious finance minister, Junius Richard Jayewardene pushed through harsh neoliberal policies, opening up the Sri Lankan economy to western powers to exploit. Farmers’ subsidies and food rations were cut.

During this time, the ACTC continued to support the government – against the interests of the Tamil workers and poor. Meanwhile, the UNP whipped up Sinhala chauvinism as a way of boosting its support, and signed an agreement with India on 18 January 1954 – the Nehru-Kotelawala Pact – selling out the tea plantation workers’ rights.

Tamil leaders retreat

Just as with the Sinhala political establishment, the leaders of the Tamil organisations reflected their class and caste background – and defended those interests. The leaders of the ACTC and FP came from wealthy, upper-middle-class backgrounds, and from the ‘upper’ caste. Their outlook was to try to win concessions for the Tamil-speaking people through negotiations with the Sinhala political establishment – and, before that, with the former British colonial rulers. They made sure that they were first in line for any privileges. The Tamil leaders were trying to grab a piece of the post-colonial cake for themselves.

This approach was based on deals made at the top – without the mass participation of the Tamil-speaking people, and without any accountability to them. Jostling for political office, and for influence over Tamil communities, the leaders of the FP made compromises with the main Sinhala-based parties – firstly, with the UNP, later with the SLFP. This led to a series of retreats on rights for Tamil-speaking people, including on the right to self-determination. The promises made by the Sinhalese political establishment were consistently broken.

It was a very volatile, at times explosive, mix. The UNP and SLFP periodically engaged in a deadly arms race for nationalism/chauvinism, each trying to outdo the other to claim to represent Sinhalese people. Meanwhile, the ACTC and FP would court the Sinhalese political establishment. It was a rotten system in which all of Sri Lanka’s workers, poor and oppressed peoples were exploited and effectively disenfranchised.

Even after the SLFP’s Samuel West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike was elected prime minister in 1956 – as the self-proclaimed ‘defender of the besieged Sinhalese culture’ – these deals continued. He introduced the Sinhala Only Act in 1956 (implemented in 1961), imposing Sinhala as the only official language of government and administration. The deals continued after the general strike of 1962, and the renewed strike wave of 1963-64.

The ACTC, FP and the Ceylon Workers Congress all supported the brutal UNP government of 1965, which launched further attacks on all workers, poor and oppressed people in Sri Lanka. FP leaders even backed the UNP’s introduction of identity cards, which was a means of controlling Tamil-speaking people. Opposition to those retreats led to the setting up of the Tamil Self-Rule Party in 1968.

Radical youth

These dynamic processes were bound to lead to big changes in Tamil politics, and had a big effect on the FP itself. The FP’s leadership was coming under huge pressure to end its compromising deal-making with the Sinhalese political establishment. It was under pressure to take a more radical stance, and to adopt policies in the interests of the Tamil masses – not just for the elite at the top.

On the basis of continual broken promises by the Sinhalese political establishment, and the failure of the workers’ movement, especially the LSSP, to put forward a clear, non-sectarian position mobilising the mass of the population in united struggle while defending the right to self-determination, Tamil nationalism was on the rise.

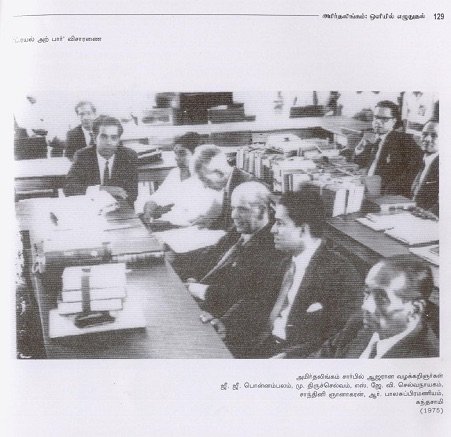

During this time of questioning, debate and rank-and-file activity, a whole series of organisations were being set up as part of the search for a way forward. At the same time, the FP leaders were being forced to shift their positions under pressure from the new layer of activists. The Tamil Liberation Organisation was set up in 1969; the Tamil Student League (acting as the FP’s student wing) in 1970 – becoming the Tamil Youth League in early 1973; Vellipullai Prabhakaran set up the Tamil New Tigers in 1972; and the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation, predecessor of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was set up in 1975. They would all came together with the FP in 1976 to set up the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF), which met and agreed the Vaddukoddai resolution. This was taking place just as the Sri Lankan left was going through a crisis, due to the LSSP and Communist Party leaders’ alliance with the SLFP government.

The students and youth were being drawn to socialist ideas, hugely influenced by Che Guevara and the Cuban revolution. Alongside other world events, including the independence of Bangladesh, this had done more to radicalise them than anything done by the FP leaders. Nonetheless, an elite layer also existed among the youth – from a middle-class, upper-caste background. They did not have a worked-out programme which could secure the rights of the oppressed masses. They did raise the need for social reforms, which put them miles ahead of the FP leaders, but they did not have a programme to achieve the stated aim of the VKR’s ‘socialist Tamil Eelam’.

When the LTTE was formed in 1976, it was heavily influenced by the VKR. Indeed, its first manifesto, published in 1978, bore a remarkable resemblance to the resolution, including its pledge, “to work in solidarity with the world national liberation movements, socialist states, international working-class parties”. Again, this was only a partial programme. As subsequent history would prove, although the LTTE was able to win significant territory, and to hold onto it for a whole period of time, it was not able to secure a permanent homeland for the Tamils.

Balance of power shifts

The 1977 general election reflected these political changes. The SLFP suffered a major defeat, only retaining eight seats. The UNP won 140. Even though the FP leaders had no intention of implementing the VKR fully, and had been pushed much further to the left than they ever intended, the FP benefitted from the radicalisation taking place. TULF, with the FP as its electoral core, won a landslide in the Tamil areas, with 18 seats.

The LSSP lost more than half its votes, and all its seats. It never recovered from this defeat – the workers and poor never forgave it for its cross-class compromises. A section of the LSSP split away and formed the Nava Sama Samaja Party (NSSP). A minority in the NSSP, under Siritunga Jayasuriya, continued to argue for a united struggle of the working masses, and stood for the right to self-determination of the Tamil-speaking minority. Siritunga would later form the United Socialist Party.

The UNP-led government – yet again with backing from TULF leaders, despite all the prior disasters – drove through its neoliberal, anti-working class, anti-poor programme. A growing strike wave gathered into a general strike in May 1980. The government was prepared, however, calling in the military to suppress the strikers. The crackdown was brutal. Leading worker activists in the trade unions were beaten up, arrested and imprisoned. Tens of thousands of workers lost their jobs.

Having crushed the workers’ movement, the UNP went on an all-out offensive against the Tamil-speaking minorities. In fact, the defeat of the general strike in 1980 was a prerequisite for Jayewardene and his cronies to orchestrate their violent campaign against the Tamils. Government ministers helped organise racist attacks against Tamils in the south – drawing on tried and tested divide-and-rule methods. Not only in the south, of course. One of the most provocative attacks – seared on the memory of Tamil-speaking people – was the burning down of the renowned Jaffna library on 2 June 1981. It was a deliberate, calculated act of sectarian vandalism by the UNP government.

Clearly, Tamil-speaking people were suffering greatly under this onslaught, living in a climate of fear, persecution and violence – the result of the growth of Sinhala nationalism, whipped up by the Sinhalese political establishment. But the Sinhala masses also lost out. They never saw any of the promised improvements to their living standards – promises made by the same Sinhala elite. Once again, they were being used as pawns in the power-struggle game.

Just three years after the suppression of the general strike, 1983 saw the violent attacks intensify against Tamil-speaking people. Thousands of Tamils were killed in the pogroms – now known as Black July. It was the final blow – on top of many other attacks, and the wanton destruction of Jaffna library and other educational institutions – pushing the Tamil youth towards armed struggle, grouped around the most resolute forces behind the VKR.

At the crossroads

The Vaddukoddai resolution had been agreed a crucial stage in the struggle for the right to Tamil self-determination. The Sinhalese political establishment trailed a long list of broken promises, and had unleashed violent force against Tamils and Tamil Muslims. Upper caste Tamil leaders had retreated, more interested in securing their own positions of privilege than rights for the Tamil masses. The left-wing LSSP, which had once organised an island-wide movement, was in disarray having compromised the workers’ movement in coalition governments.

In the light of this and drawing inspiration from radical developments around the world – such as the Cuban revolution, armed struggle in colonial countries, Bangladeshi independence, and mass workers’ movements – radicalised Tamil youth took the road of armed guerrilla struggle. It was an understandable decision.

Yet, today, we again stand at a crossroads. The same question is begging for an answer: which way forward for the struggle? The difference is that there are many lessons we can learn from the 68 years since Sri Lankan independence and the 40 years since the VKR.

The fight for Tamil rights has never gone forward on the basis of deals at the top with the political elite, whether with the British empire or the Sinhalese political establishment. The best that approach can achieve is some privileges handed to a handful of self-proclaimed Tamil leaders. The same applies in the diaspora.

It is essential to understand who the Sinhalese political establishment really represents. Despite all its cynical claims – and those of its most extreme and reactionary elements, like Mahinda Rajapaksa and the Buddhist-chauvinist-nationalists – it does not represent the majority population. Most Sinhalese people are exploited workers and poor.

The current Sirisena/Wickremesinghe government is driving through attacks on the living standards of all workers and poor in Sri Lanka. It is privatising vital public services. It is cutting back on jobs and subsidies on essential food and fuel. It has launched a massive attack on education. It is, in fact, a neoliberal programme in the interests of the top 1%, with the backing of the International Monetary Fund, and western and regional powers. That is raising anger and opposition among Sinhala workers and youth against the government and political establishment.

In the meantime, the land grab in the north and east continues. Tens of thousands of Tamils continue to languish in camps for internally displaced people. Tens of thousands are still unaccounted for since the end of the war in 2009. Secret detention centres are known to exist. Tamil women in particular continue to live in fear, vulnerable to physical and sexual violence, above all from military personnel who act with impunity.

Despite this oppression, however, protests by students have taken place – against attacks on education, as well as against rape and sexual violence. These courageous acts have been met with harsh repression by security forces. It is impossible, however, for any government to put down a whole people.

United struggle

Tamils are not alone. The Tamil Solidarity campaign believes an important part of the fight for Tamil rights is to link up with our natural allies. In Britain, that is the six-million strong workers’ movement organised in the trade unions. It includes people fighting back against the Tory government’s austerity and job cuts, and campaigning in defence of the health service and education, against racism and discrimination. It has seen a political expression in the enthusiasm of many Tamils when Jeremy Corbyn – a long-time support of Tamil rights, and of Tamil Solidarity – was elected leader of the Labour Party.

It also means linking up with other oppressed people. There is a world of resistance. Just a few examples would include the struggle for Kashmiri self-determination, or that of the Kurdish people, or in Bangladesh where thousands of people face eviction to make way for Chinese coal mines. It has been seen in the US where people are rallying in their tens of thousands behind the socialism of Bernie Sanders.

Tamils must have the right to self-determination, including a separate state if that is their choice. And the rights of any minority in any area of Sri Lanka must be respected, without fear of persecution or discrimination. The right of Tamil self-determination must also be recognised by the workers’ and students’ movements in Sri Lanka. A united island-wide struggle of the organised workers, alongside the poor and oppressed, would be the best way of defeating the present government’s neoliberal programme. It would be the basis for overcoming the reactionary, divisive forces of Sinhala chauvinism and nationalism. Such a movement could also guarantee Tamil self-determination based on cooperation and solidarity.

[/box] [blank_spacer height=”20px” width=”1/1″ el_position=”first last”]